Today in the Dakar the precious motorbikes are recovered by helicopter. Before they used to become buoys in the desert. They were stripped. Cars were reduced to skeletons, because everything is recycled in Africa. That was the Paris-Dakar, the real one: 14,000 km north-south.

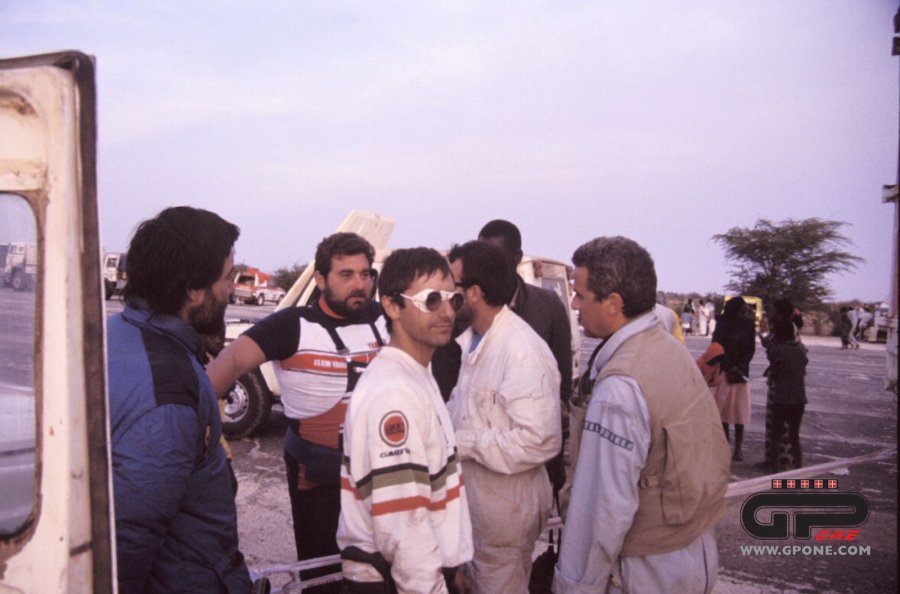

It happened in ... who remembers the year? I only remember that we were in the car, Gigi Soldano and I, following the Paris-Dakar, in a very special press car: a Mercedes 280 GE which with Klaus Seppi and Maurizio Arrivabene had finished sixth overall in 1987.

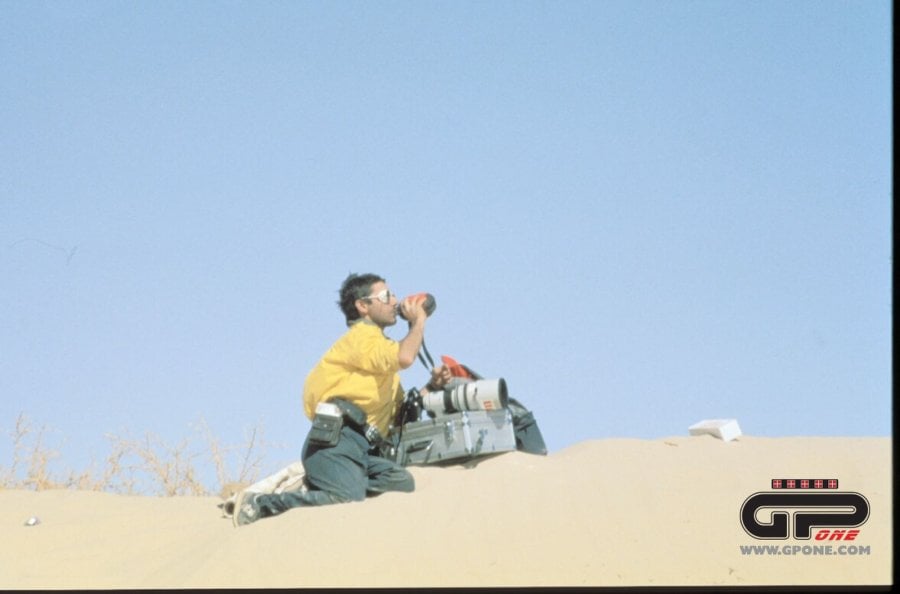

That 4x4 used to go very fast so, after setting off in the night and finding a good spot after sunrise to take some photos of the fastest riders, we could get back on the track to look for some other nice places to take photos. This is how our Dakar worked: four, five stops, to shoot motorbikes, cars and trucks, until it was too dark to get good images. And then we had to continue in the night, on the tracks devastated by the competitors, until the flashing light at the end of the stage appeared in the distance, which meant the bivouac was close, with a hot meal at Africatours and a few hours of sleep before setting off again.

They were long days, but we were young and enthusiastic and every now and then we even got some nice photos at night, like when in front of us a car that became the cover page for Dakar overturned and caught fire! Dakar!

On that occasion, however, it was still daytime and the 180 hp six-cylinder petrol engine was purring along loudly while the four Michelin Desert tyres were biting the sand when, just off the track, we saw Findanno's Yamaha Ténéré. We did not know yet, of course, we found out during the night, but Giampiero had crashed, picking up a head injury and had to abandon. His bike, however, appeared intact. We stopped.

A quick look around the bike was enough to confirm that it had no apparent damage. And since at the time starting the bike with the crank arm was commonplace, I fired it up. The engine idled regularly.

"I want to try to take her to the bivouac". I said it impulsively, without even thinking about it and without giving Gigi time to reply.

A crash helmet, even for us, was mandatory, I put it on. In the saddle, I almost touched the ground with the tip of my foot and half-sitting out of the saddle. I realized that without motocross boots it would not have been a very comfortable ride but, as I said before, we were young and Dakarians. I started off. With all the recklessness and the desire to seize any opportunity that stood before us. A journalist, but above all a motorcyclist, albeit with virtually zero off-road experience except for some regular outings with my friends Francesco, Guido and Dionisio.

I rode standing up on the pegs, as I had seen Franco Picco doing and I was already imagining my arrival at the bivouac, where I could hand over the bike to Yamaha for whom it would have been a precious replacement for its riders. But I only did a few kilometres.

Riding standing up in the sand is not so easy, any more than leaning over at 65° and touching with your elbow. You have to keep the throttle open to make the front wheel float on the sand and spring on your legs like on a horse. Well, among my many sports as a pentathlete there was also horse riding, but after a few kilometres my legs began to give way: I was riding and trying to forcibly control the bike, instead of making it float over the sand, so I started to rest my butt on the saddle. And every time I did, I slowed down and the front wheel sank. At that point I reacted by grabbing the handlebars harder. I think I realized that day what happens, in the ring, when your arms and legs start to hurt and don't allow you to move easily. It is then that you realize which of the two boxers will end up getting a pasting.

"Stop! Get off!", Gigi's voice came firmly from the 280 GE.

"I'll just do a few more kilometres, then I'll rest", I yelled back, unconvinced.

"Stop, otherwise instead of the bike I'll be bringing your dead body back!", Gigi retorted.

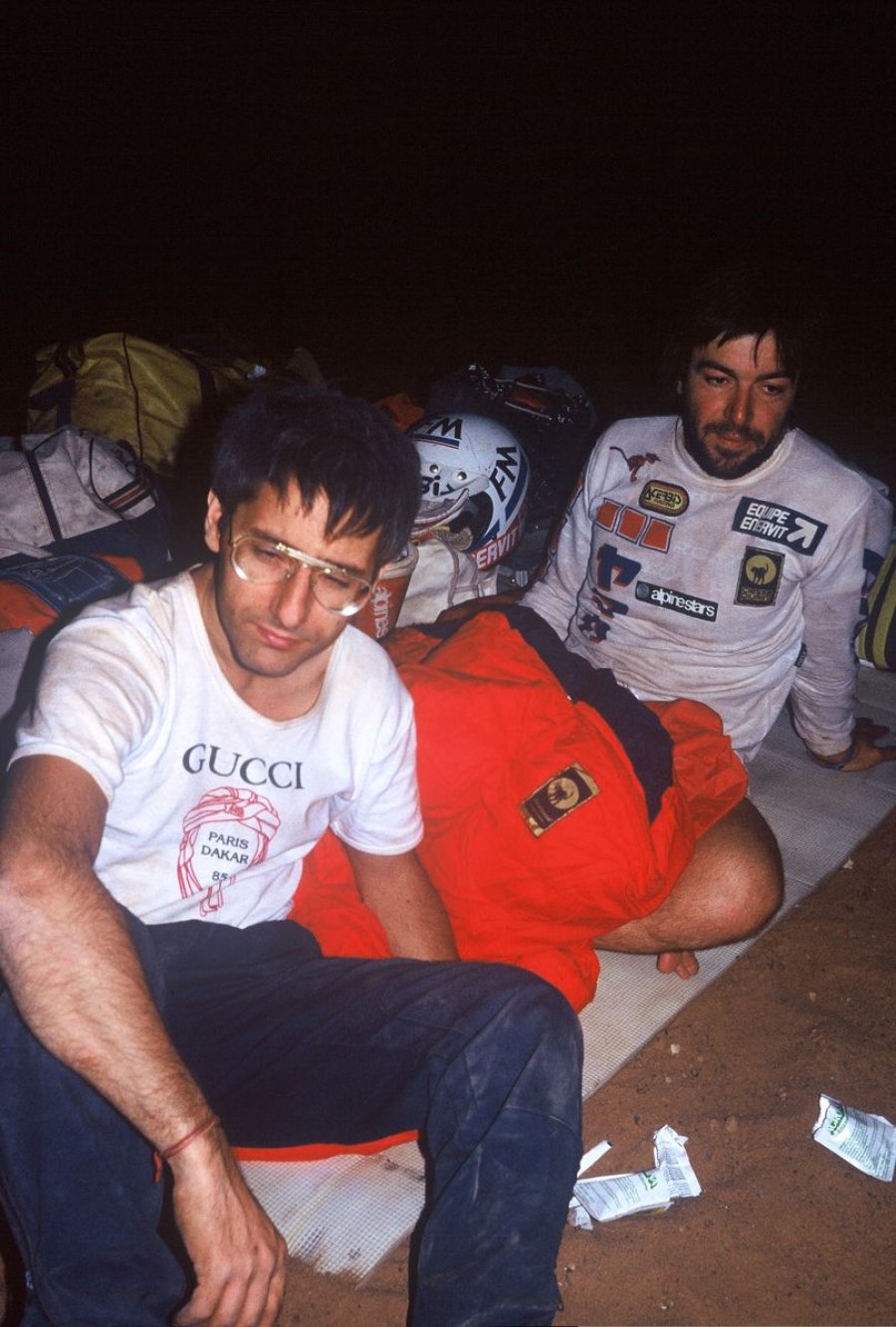

That sentence was the equivalent of throwing in the towel from my corner. It was like seeing the rags fly and I didn't like it but I stopped, sweating. David Bowie came to mind: We can be heroes, just for one day. But it wasn't to be, this wasn't going to be the day. Gigi got out of the car and helped me push the bike into the sand just off the track. Then with the help of the on-board tools we took the single-cylinder engine apart and the wheels. Precious spare parts. We marked the position, knowing full well that the bike was unlikely to be recovered.

When we set off again it was like leaving a friend on the ground with a broken leg. I couldn’t take my eyes off that dust-covered motorbike dwindling away into the distance. I wouldn’t have seen the flashing light at the end of the stage. I wouldn't have been welcomed as a hero for recovering a bike, but we still had something.

A single cylinder and two wheel rims was all we saved that day. But it was still something. I could not say I was satisfied, my ego had emerged bruised and battered by that attempt but in the evening, as I slipped into my sleeping bag, I convinced myself that when I got back, I’d do some off-road outings. Who are you kidding...