There was always a lovely light when racing in Kyalami. At an altitude of 1,500 meters, the air was clean, and it was nice to lean against the old pit lane wall to watch the riders racing in the 500 rush along the straight with their engines roaring and their bikes scoffing as they crouched behind the front fairing to be as aerodynamic as possible.

They darted like giant colored hornets, and I imagined being on a bike, bent over behind the Plexiglas, with my nose almost pressed against the rev counter, breathing the hot air from the radiator instead of standing there with a notepad in my hand. It was like being at the racetrack to see the horses coming around the last bend, hoping to have the winning ticket in your hand. At every lap, your heart accelerated.

They darted like giant colored hornets, and I imagined being on a bike, bent over behind the Plexiglas, with my nose almost pressed against the rev counter, breathing the hot air from the radiator instead of standing there with a notepad in my hand. It was like being at the racetrack to see the horses coming around the last bend, hoping to have the winning ticket in your hand. At every lap, your heart accelerated.

It was 1992. Wayne Rainey was fighting for the World Championship title in the last race. To win, he would have had to get ahead of Mick Doohan, in a better position than the sixth. It wasn't guaranteed but, nevertheless, he had refused the help of his teammate, Jon Kocinski, offered to him by Kenny Roberts.

Wayne Rainey was fighting for the World Championship title, but I was there for Eddie Lawson's last race.

These things were spinning in my mind. I should have written about them, but, even if the duel for the title was exciting, it really didn't interest me. In fact, I knew that this would be Eddie Lawson's last race on the Cagiva. He would no longer continue to race after that.

So that Grand Prix in South Africa was kind of a last show, and I decided that I would enjoy it to the fullest.

That's why I had become a permanent presence in his garage during that the weekend. We had become friends when he started racing in Roberts' team in 1983. After the tests or the race, Giacomo Agostini, who managed the powerful Marlboro-Yamaha team, would welcome us into the motorhome with the two riders, but all the questions were obviously for King Kenny.

Eddie kept quiet, but I would make it point to get him to talk.

Eddie almost always kept quiet, still in his suit, standing to the side like a wallflower. Maybe he didn't give a damn, maybe he even preferred minding his own business instead of answering the questions those pain-in-the-ass reporters spewed, but would drag him into the conversation anyway.

Eddie almost always kept quiet, still in his suit, standing to the side like a wallflower. Maybe he didn't give a damn, maybe he even preferred minding his own business instead of answering the questions those pain-in-the-ass reporters spewed, but would drag him into the conversation anyway.

I would make it a point to get Lawson to talk. He would greet me when I entered his field of vision. He knew that, in the end, I would ask for his opinion on the championship, on the performance of his bike, on most everything.

He was rather introverted at the time, catapulted from the American racing world to the European racing world of the so-called "Continental Circus". After that first season in 1983, Lawson revealed himself for what he was: he beat Freddie Spencer, the champion who had dethroned his team leader the year before and stashed away four world titles under his belt.

In those days, I no longer asked questions to help him out and be more comfortable around people he didn't know... or so I thought. I would stop him after the Grand Prix. Sometimes I helped him take off his suit by pulling on his sleeve. When he would get off the podium, if he had a trophy in his hand, he would pass me his helmet while we walked towards his motorhome.

After the race, regardless of how it went, he didn't like having people around, but he put up with me.

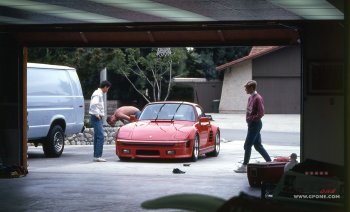

After the race, regardless of how it went, introverted as he was, he didn't like having people around, but he would put up with me. We talked about races - maybe not about that recent race - about sports in general and how much he longed for California, which he used called the "real country". He would describe it as the land of the perpetual sun, while in England at Donington, in Germany at Hockenheim, or in Holland at Assen, it always rained. When he invited me to his house in Upland one summer, and it was raining, I had fun teasing him about it. But I have to say that the ride through the Mojave Desert the following day, with him on a Yamaha 250 two-stroke motor cross bike and me riding a much tamer 350 four stroke, was magnificent. That was one of the best memories I have from those years in the World Championship, even if I fell so many times that I was sore for a week.

I think Eddie was the best rider I have ever known. I had seen the last few of Ago's seasons. Just like everyone else, I was surprised by how nice and subtly witty Barry Sheene was and, of course, King Kenny's win in the 500 totally stunned me, as did Freddie Spencer's class when he made everything seem so easy. But Lawson was something totally different. What struck me most of all was that it always seemed like he wasn't racing for the world title. Instead, it was as if he had to vent some internal energy when he raced that might, otherwise, go to waste.

Maybe he wasn't the rider with the most crystalline talent among the many champions of the time, but he really, truly wanted to win, and he really, truly hated to lose, so much so that he dedicate every last drop of energy to racing.

His favorite nickname was Awesome Lawson ... pronounced like an American, of course.

It's what he used to called "the need for speed". That fever that he fulfilled with fines, "tickets", that fluttered around and filled that van he rode around the US in. Going slow for him was not an option he contemplated. But once he got on a bike, even in the most convulsive Grand Prix races, he rode so cleanly that you hardly noticed he was at his limit. And, because he hardly ever fell, they started calling him "Steady Eddie" but was also known as Awesome Lawson. Pronounced like an American, of course. It was definitely the nickname he liked best. The only one that seemed to boost his ego.

So, that day at Kyalami, during his last race, instead of going under the podium to applaude Kocinski's victory and Rainey's third title, I ended up in Cagiva's red brick garage.

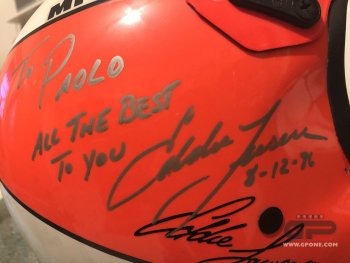

Eddie stood on two sheets of newspaper, already in plain clothes. He hadn't finished the race and was putting away his suit, already folded, in his bag. He raised his head, looked at me, and without speaking, he continued putting his things away. His boots, his gloves. Then he carefully put away his helmet, so he'd be able to effortlessly close the long zipper. But before doing so, he got up, as if he were about to say something.

I had my notepad tucked away in the belt of my pants, behind my back, like I always did, and my Canon around my neck. But there were no photographs or notes to take.

I felt slightly uncomfortable, like someone who accidentally opens a door and finds himself witnessing something he shouldn't have seen. But I didn't move.

I've won enough.

I've lost enough.

I've hurt myself enough.

I've had enough.

He said it, pronouncing every word slowly but in one breath, but it was a hell of statement. And, before the meaning of what he said exploded in my mind, Eddie Lawson bent down, pulled the zipper of the bag closed and walked past me.

I stood there a few minutes while he said good-bye to the mechanics, one- by-one.

I only followed him with my eyes this time, until he stopped for a moment, the outline of his figure backlit against the door that led to the paddock.

Author's note

I don't remember how long ago I wrote this article, but every time I come upon it, I feel the warm, hard surface of that wall at Kyalami and hear the roar of the 500 two-stroke.

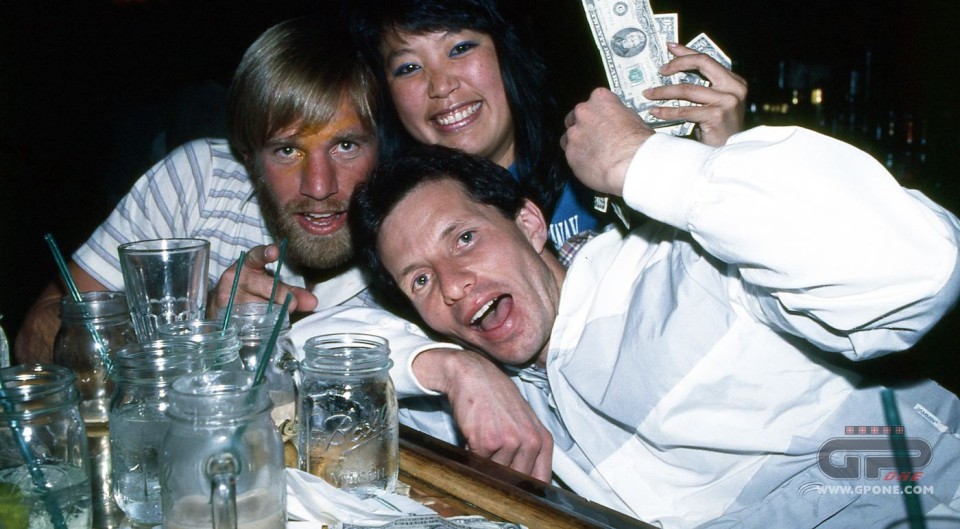

It came up on my Mac while I was looking for something else, as did some of the photos taken by Gigi Soldano that weekend in California at Eddie's house. Like shipwrecks brought back to the surface by the waves. Images taken from very old Kodak film transferred to digital. Ghosts. What memories do I have of a rider like Lawson? Well, the photo at the beginning of this article dispels all tales about him, don't you think?

Eddie Lawson was not commemorated enough during his fantastic career. At least he wasn't in my opinion. But maybe he really didn't give a damn about it. One thing's for certain. As far as I'm concerned, the image I have of him is very different from his public one. Maybe because of that extra bit of attention I had always reserved for him when he was a rookie in the World Championship. By the way... he deserved it.