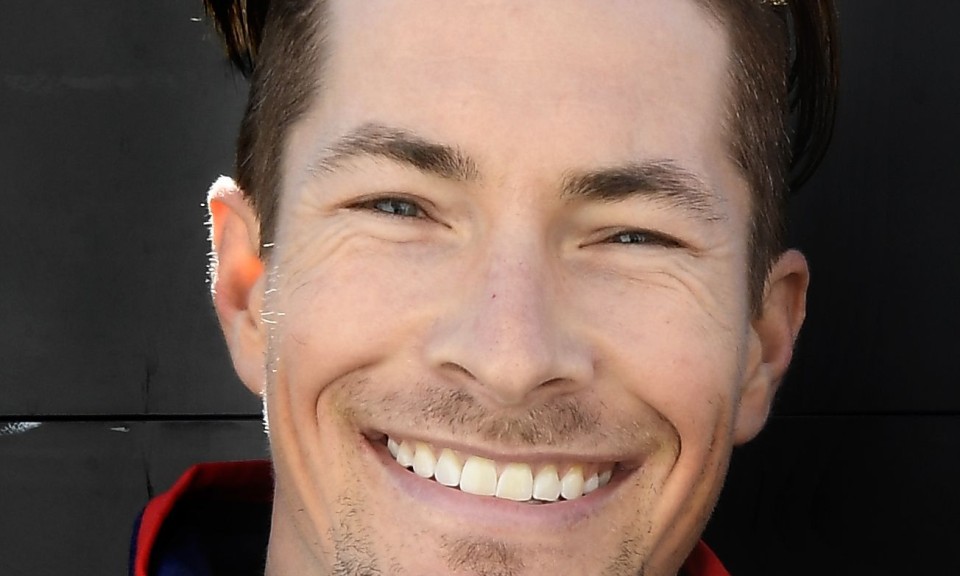

Several years have passed now, but I will never forget something Nicky Hayden once did. I had returned to the Grand Prix races after a difficult moment in my personal life, carrying with me that fragile quality that follows a rough time. I was feeling a bit uneasy, so I went into the Ducati garage for a coffee, and he saw me before I saw him. I could tell from his movements that he was asking a girl on the team if he should come over and say hello to me. Then, on receiving a positive reply, there he was before me, hand outstretched and a big smile on that handsome, all-American face. His was a smile that came effortlessly, and it made the girls who met him swoon: that sparkle in his eyes never faded.

He held out his hand, shaking mine. “I just wanted to see how you were doing”, he said. There was nothing forced about his gesture and I recognized his expression. It was a sort of shy embarrassment combined with that look like he wanted to explain how the day had just gone that way – a little off – and that there was nothing he could do about it. That tomorrow he would go faster. That it was a rider’s destiny to go through good and not so good moments, but that he would keep going, believing in himself without ever making excuses. It was a philosophy tailor-made for racing, but it was also his philosophy of life and one with which I fully agreed. All together, each on his own trajectory, always toward the same goal.

We stayed like that, facing one another for a few moments, saying things that I don’t remember now, things that most likely were not of much importance. But that was not why he was there. He was there simply to make me feel like we were not rider and journalist on two different fronts, on opposite banks of the river, but together in the same boat, driven by the same current. In short, two human beings.

I met him for the first time in 2003 in the Honda garage, where they had chosen him as Valentino Rossi’s teammate. A 22 year-old who had made a name for himself by winning the American Superbike championship, who was then catapulted onto the European scene. “Why do I ride as number 69? Well, it’s a number that you can still read when the bike is upside down after a crash,” he joked with me. He made it easy to laugh with him.

His father, Earl was there too, the patriarch of a family fully dedicated to motorcycle racing: big brother Tommy, Nicky, the middle son, followed by Roger Lee, and then two sisters, Kathleen and Jenny. Earl spoke with an American accent that I found difficult to understand, but he told a story of the whole family touring the States in a camper-van crammed with bikes and spare parts, racing on a different flat track every Sunday. At the end of each season, Tommy would pass down bike and gear to his little brother, who in turn would pass it down to the next in line. That meant that sometimes Nicky found himself racing a junker and wearing patched leathers. In spite of it all, he had gone from win to win with his family around him until abandoning dirt for paved tracks and winning the AMA title (American Motorcycle Association). It was then that the call came from Honda. Destination: World Grand Prix Motorcycle Racing.

Years had passed since that first meeting – no less than six – and in the meantime, Nicky had achieved his dream of winning the MotoGP World Championship, beating out none other than Valentino, his ex-teammate. It had been a fiercely fought season, with several upsets and sensational strokes of hard luck for them both. So after Nicky had crossed the finish line, wrapped in the American flag, he wept. It was an uncontrollable, desperate weeping. “What would have happened if I hadn’t won that title? I would probably have turned into a bitter old man,” he admitted, without any effort to conceal that this title, which he then celebrated by racing with the number one on his top fairing the following year instead of his iconic 69, was somewhat the goal of his life.

A simple life, in his way of thinking. In his hometown of Owensboro, on a plot of land where some years ago the name of the road was change to carry his family name. I’ll admit it: I’ve always had a soft spot for American riders, from Kenny Roberts, the man who launched another dynasty as the first to win a 500 championship in 1978, to Eddie Lawson, all the way to Wayne Rainey, Kevin Schwantz, Freddie Spencer and Randy Mamola. The reason is that I have always seen true sportsmen in them. They're trained to be athletes, of course, and I admire them for that; but in terms of sportsmanlike conduct, Nicky Hayden was the best of them all. Never a word spoken out of turn, never a rude gesture. We all remember him screaming in anger back in 2006, when he was dragged to the ground in the Portuguese Grand Prix by his then teammate Dani Pedrosa, who risked causing him to lose the title. It was part of that fiercely fought season I mentioned. But ten minutes later, Nicky had already donned his classic smile, and neither he, nor his father Earl by his side, said another word about it. It wasn’t as if they were practicing self-restraint. They were both simply aware that sometimes life holds unpleasant surprises and we need to face them.

Naturally, there were many good times that Nicky also shared without trepidation. Like last winter, when he had his photograph taken in Venice aboard a gondola while asking Jacky – the petite, quiet Jacky, always respectful of a rider’s space – to marry him. A romantic gesture, most certainly spontaneous, since he apparently could find nothing better to wear for the proposal than a camouflage jacket! They probably would have been married over the summer, between one race and the next, Nicky and Jacky.

Hayden had not raced to live for many years, but he certainly lived to race. And no, no matter how his career might have unfolded, he would never have become a bitter old man.

Translated by Jonathan Blosser

This article was published on Corriere dello Sport